It’s a dreadfully dreary day in Montreal and while I’ve been trying to cut out the alliteration, it really does call for it today. As such, I have no real reason not to write a post— I’ve been procrastinating all day. Why? Well, my reading is a month ahead of my posting. Since Big Swiss I’ve read eight books so this will be a two-for-one deal: a review of two Nick Drnaso books, Sabrina and Acting Class.

Beverly was the Drnaso book that first ended up on my TBR list a while back, maybe because it won Best Graphic Novel from the LA Times in 2016 or maybe because when you live beside Drawn & Quarterly you sponge up graphic novel news. I fully intended to start with Beverly but it’s a harder title to snag at the library, in between other people’s hold requests. In any case, both Sabrina and Acting Class were available. And let me tell you, I was not ready.

Often, I go into a book relatively blind. The summary pitch on the back is rarely what sways me. Usually I’ve decided to read a book before I’ve seen the back flap. If I’m browsing, I pay attention to the blurbs insofar as who, and from which publications, wrote them. My high school English teacher once told me that finding good books is easy, even if you don’t have any friends, because you actually only need to find one good book. If you really like Shirley Jackson, then read who she read: Ralph Ellison, J.D. Salinger, Dylan Thomas. Ellison might take you to Langston Hughes, Ralph Emerson, T.S. Elliot, Thomas Hardy or James Baldwin. Salinger would take you to Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Thomas would take you through quite a lot of people as he had peripatetic taste (typical poet). This is a long way of saying I didn’t know anything about Sabrina before I started reading it but I wasn’t disappointed.

The book opens with a standard exchange of updates between Sabrina and her sister in their parents home while Sabrina is cat-sitting. This is the last time we see Sabrina, though the book is defined by her negative space. The fact that the conversation is banal is exactly the point: the reader does not know Sabrina. We know her by sight and by name but we don’t know who she is, how she feels about her relationships, or where her politics lie. But she seems nice; she laughs easily. The narrative cuts to Calvin Wroebel who is just ending his shift on a military base. Calvin has an old friend, Teddy, visiting him who is going through a terrible ordeal: his girlfriend is missing. What unfolds is an exploration of how one family’s tragedy can become an allegory for a nation, how the media becomes festering hotbed for conspiracy theories, and how easily we avoid confronting hard truths in the face of our private sadnesses.

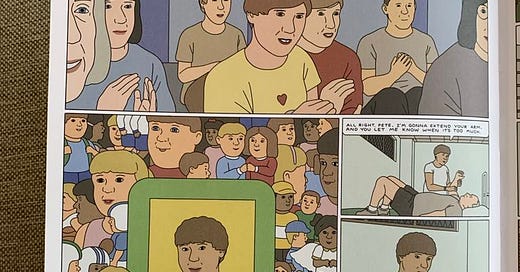

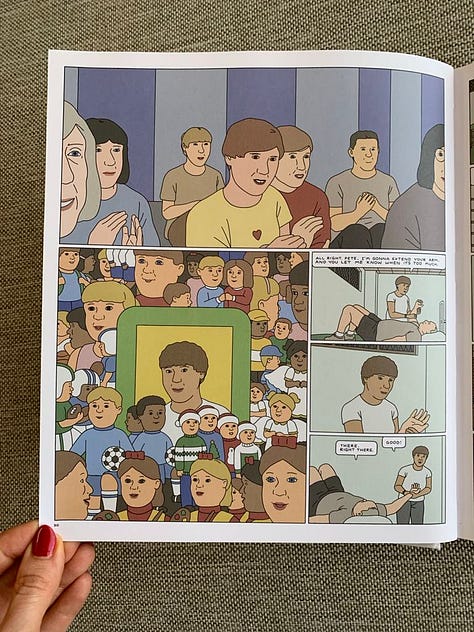

It’s incredibly affecting despite a rigid artistic style. Stylistically, Drnaso reminds me of Dan Climan’s paintings. The parking lots are too orderly, the road is too free of litter, colours are muted. There are a lot of thin straight lines. Drnaso told BOMB magazine that he’s “more concerned now with solid cartooning and transitioning from one panel to the next.” That stripping away is more effective than adding things in is an old precept but it remains hard to strike the right balance. Drnaso’s instincts were right, at least for these stories. The cleanliness of the drawings contrast with their emotional import creating a profound sense of unease due to an excess of containment. You’re never sure where the story will go next because all it’s possible directions seem to be roiling just below the surface, ready to boil over or fizzle out. Much of the book is about grief but Drnaso’s touch is light. Just as we can’t know a grief before it comes for us, we don’t know the grieving characters. Teddy has no recognizable personality traits. A lot of his time is spent gazing. Pain is conveyed through silences and blank expressions. Because the characters’ facial features are quite literally dots and a clean line, when the placid facade breaks into anguish it’s genuinely wrenching. It’s a twist of the heart, something shouted, something released.

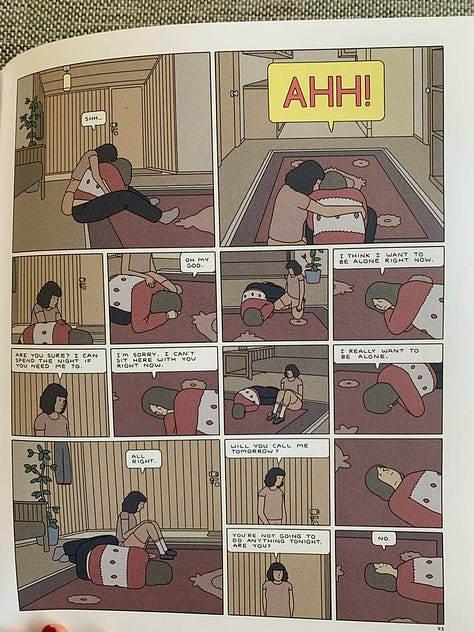

Acting Class ramps up the unease, adds some creepiness, and subtracts some of the realness. This book is more recognizably fictive and outlandish. There are a lot more characters, all of whom seem to be slightly out of step with their lives. Whereas Sabrina sits in it’s emotion, Acting Class has a lot more momentum. There are richly illustrated panels here, filled with objects and details. This is not to say that Drnaso abandons his style. In Acting Class, some characters have eyes with irises, distinctive teeth, wrinkles, a hair style. The books follows a ragtag group of adults as they embark on a community centre acting class led by an unconventional and unpunctual teacher, John. John tells the group they have all joined because they are lonely and missing something in their lives— a diagnosis that many characters object to. Nevertheless, over the course of four weeks, problems the characters have been studiously ignoring in their lives begin to come to a head. The lines between acting and reality begin to blur and become more bizarre as John’s exercises ramp up in intensity.

I wasn’t totally sure what to make of Acting Class when I first finished it. I mean don’t get me wrong, it’s really really good. It’s stranger and more insular than Sabrina, which did that “capturing the zeitgeist” thing so well. At the same time, many of Sabrina’s themes are present here too, in an alchemized form. In both, we find characters struggling to connect to others and to themselves; to feel and be present and self-aware. And in both books, characters find their way through by anchoring themselves in the ordinary. When characters begin to live in their own minds more than in physical reality, they tend to lose their grip. This seems to track as Drnaso tells the Guardian that he finds that “something about comics attracts people who have anxiety or OCD-like tendencies.” It’s the painstaking work of creating that grounds Drnaso. He loves the engagement of the process, not the ‘reward’ of public accolades. In 2019, he told the NYT that he “fucking hates [Sabrina], [that he] never should have made it.” Which, he almost didn’t. At the last moment, he stopped Drawn & Quarterly from their production process, had a breakdown, then let them print it. It went on to be the first graphic novel to ever be nominated for the Booker Prize leaving D&Q scrambling to meet demand.